- Home

- Naben Ruthnum

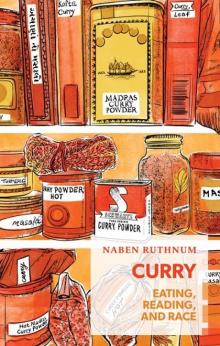

Curry Page 3

Curry Read online

Page 3

In memories and stories, the diasporic household often becomes a stand-in for the land of origin, a circumscribed set of walls that bound in language, scents, tastes, ethical codes, and patterns of love and communication that start to shimmer and vanish if the front door is left open too long. It’s a backdrop to the stories, one encountered so often that I distrust my own household recollections sometimes, as though one of Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s short stories or a Sri Lankan pal’s childhood anecdote has supplanted my memory. But the paper my mother pinned up wasn’t a signet of the unreachable past: it was a set of dumbed-down instructions for a boy who had been spoiled nightly at the dining table.

Growing up, I always knew there would be food on the table, in the fridge, a delicious and seemingly inexhaustible supply. Toothpicking the paper to the wall marked a break. For me, the act of cooking was to be about self-sufficiency, adulthood – not a reanimation of childhood. That’s what eating is for: manning the pots and pans meant taking the reins of adulthood, a common factor in many immigrant stories and essays – like the one I’m telling now, like Koul’s and Lahiri’s. But self-sufficiency was the stated purpose of cooking when my mother was making sure I learned how to feed myself – there were no secrets, no arcane codes held back from one generation to the next only to be revealed through hardship, experience, and a moment of deep eye contact signalling admittance to the secrets of our ancient race.

The second curry of note I’ll mention is Homecoming Shrimp Curry, which has become the staple meal I associate with Christmas in the Ruthnum household. It’s shouldered aside kleftiko and a Persian fish dish with a walnut stuffing as the go-to son-pleaser for my annual returns home, and my parents like it just as much as I do. It’s a deep greenish-brown, a shade you don’t often see in Indian restaurants outside of perhaps a saag: while Westerners may like brown food, they don’t like it to actually be brown. The sauce has a density earned by its ingredients and process: Mom makes the masala with large, motherfuckering onion chunks that would be the star of the dish if the sauce didn’t take a midmorning whirl through the food processor before being returned to the pan. The huge shrimp, decanted frozen into a colander from a frozen bag, look like chilled practical effects from a 1980s alien-invasion movie before the sauce catches up to them and they’re subsumed into the curry, white and pink peaks in the murky simmer.

Time and varying heat are key to this dish’s success, a daylong process of heating, settling, cooling, and boiling whose alchemy seems beyond science. That’s often part of curry narratives, too: the ineffable, inexplicable Eastern magic performed on electric Western stoves. Top British chef Heston Blumenthal, on his television show In Search of Perfection, where he sought to make perfected versions of classic dishes such as hamburger and steak by seeking out their ur-versions and distilling historically successful processes into a measured, modern method, had scientists do a study on the use of yogourt in the marinade for chicken cooked in a tandoor for his tikka masala episode. While it was proven that yogourt vastly aided the marinade’s absorption, they couldn’t figure out why. It just did. While this made for an irresistible TV moment, and I don’t doubt Mr. Blumenthal’s standards or the BBC’s scientist-hiring resources, it strikes me as odd that what seems like a simple matter of chemistry and biology should be insoluble.

There’s no magic or formula involved in the time and heat factors of Homecoming Shrimp Curry, but there is particularity. As in many immigrant households, one of my parents prepared food in the morning and reheated it throughout the day, the knobs on the stove and eventually the button on the microwave enduring twists and pokes as mealtimes came around. In the case of this curry, the multiple simmerings are what elevate it to Christmas dinner and my first off-the-plane meal. The basics are simple, and as I can’t think of a good reason not to include the recipe, I’ll give it to you. Here’s a direct paste of the email that Mom sent me so I could botch the making of the dish:

Kay’s Madras Prawn Curry

Ingredients:

Large prawns … cleaned and ready

2 large onions … peeled and puréed in the food processor

Coriander leaves washed and chopped up

Tamarind soaked in warm water

Turmeric

Methi … seeds or fresh

Curry leaves … if available

Garlic and ginger about a heaped teaspoonful each

Fish curry powder … (I buy the fish curry powder from Super store). You can use the regular or your own mix as well. About 3 tablespoons or more … it all depends on the size of the onions …

Water or coconut water

2 tomatoes, chopped up

Salt and chilies

Method:

In a large pan heat some olive oil, sauté the prawns with a sprin kling of turmeric.

Do not overcook the prawns.

Remove and put aside.

Throw away the liquid.

Heat up some more oil, add the puréed onion … stir till softened and lightly browned.

Make a pit in the middle, add the curry powder mix (tamarind, curry leaves, methi, ginger, and garlic in some warm water).

Add a little bit of olive oil on top and let cook on low heat.

Allow the curry to cook thoroughly with the lid on … but checking often … add a little water or coconut water to prevent sticking … then mix the onion with the curry … Now is the time to choose the thickness of your sauce … this should be a fairly thick one. Add the chopped-up tomatoes.

Let simmer for a few minutes.

Add the prawns.

Simmer some more.

Add your chopped-up coriander and serve with rice or rotis.

I called to inquire about the accuracy of this recipe, and it turns out my recall was wrong: Mom does food-process the onions before the cooking starts, not after. The pureeing-of-the-completed-sauce thing comes, I realize, from a Gordon Ramsay chicken tikka masala recipe I used to make all the time when I lived in Montreal, with a roommate who had a Cuisinart. Mom also leaves out the bit about time lapses and reheating throughout the day, but that’s hard to quantify on the page. I don’t follow the turmeric-fry step of the recipe – seems to me that the shrimp cook so fast, they should do it in the gravy where they belong. Then again, my dish somehow isn’t a patch to Mom’s: this is a trope, yes, but it remains true here – I know I can fix it if I master the timing.

There are some moments in this recipe that an Indiancuisine purist would find harrowing. For example, the ‘fish curry powder from Superstore.’ At the popular food blog Food52, Bay Area food writer Annada Rathi rails against these concoctions: ‘That’s when I feel like screaming from the rooftops, “Curry is not Indian!”; “Curry powder is not Indian!”; and “You will not find curry powder in Indian kitchens!”’ She’s certainly been in more kitchens in India than the zero I’ve entered, so I’ll take her word, but I’ll tell you this: every diasporic kitchen I’ve opened cupboards in contains curry powder, even if it is a home blend of dry spices tipped into an old Patak’s screw-on glass jar. Rathi isn’t a hardliner – she goes on to note that ‘in the course of this article, it has dawned on me that “curry” is the most ambiguous and therefore the most flexible word, a broad term that conveys the idea of cooked, spiced, saucy or dry, vegetable, meat, or vegetable and meat dish in the most appropriate manner available.’ The spectacular imprecision of the term speaks to its ability to encompass centuries of food history, cooking, misinterpretation, and reinvention: it’s truly the diasporic meal, even when it stays at home. Curry is only definably Indian because India is a country that has the world in it.

There is a truth to the tropes of cooking and homeland and curry, but it can’t possibly contain the entire truth: the overlaps in this conversation between writers like Lahiri, Koul, and me are vast, covering our relationships to our parents and a land we barely know compared to the countries where we wake up every day. In the details, the distinct efforts to set personal experience apart – my i

nsistence that Mom has no kitchen secrets and that cooking was never meant to be a key to the exotic but a passage to adulthood, Koul’s universal reflections on whether there is a point when one ever stops needing one’s mom, Lahiri’s foray into cookbook learning – are there, but I wonder if they are present for readers who are drawn to and receive these pieces. Are the brown, diasporic readers looking for commiseration? And are the non-brown ones looking for an exotic, nostalgic tour of a foreigner’s unknowable kitchen? The short answer, I believe, is yep.

The introductions to Indian cookbooks often trade on the authenticity of the author’s experience and past – their true knowledge of real Indian food – while gently maligning what passes for Indian food in the West. Meena Pathak, who married into the family behind the Patak’s brand, started a line of authentic Indian cookery books after being ‘amazed by what people in England viewed as Indian food.’ The sauces, spices, and pickles that have been produced by Patak’s in the U.K. since 1957 are often a touchstone for Indian food that falls short of the authentic mark, though Pathak calls the company a maker of ‘authentic Indian snacks and pickles,’ perhaps deliberately leaving out the sauce and spice-paste component of the family business.

Patak’s produces a lineup ranging from korma to jalfrezi to tikka masala that perfectly reflects the crossover point between the curries that South Asian immigrants to the U.K. popularized in the 1970s and Anglo-Indian cuisine, which arose during the Raj in India as ‘Indian cooks gradually altered and simplified their recipes to suit British tastes,’ according to Lizzie Collingham. Under British rule, Indians transformed the Mughal dish qurama, initially made with Persian methods described by Collingham as ‘first marinating the meat in yogurt mixed with ginger, garlic, onions and spices before simmering it gently in the yogurt sauce. The mixture was thickened with almonds, another Persian trick.’ Anyone who’s marinated and BBQ’d the non-tandoor cooked version of tandoori chicken will recognize this yogourt bit as a technique that became a mainstay of Indian cuisine. In eighteenth-century Lucknow, as the Mughal Empire declined, dairy was added to many of the dishes that the empire’s Indian cooks had been altering for decades, creating a creamy korma that more closely approximated what you’ll find in a Patak’s jar nowadays. Cooks in the princely Oudh State courts of Lucknow also incorporated further modifications picked up during the Raj years – ‘coriander, ginger, and peppercorns which were basic ingredients in a British curry,’ writes Collingham. She attributes the innovations in Lucknow to efforts on the part of the Oudh rulers to prove their distinctive value as a cultural capital to rival the Mughal court in Delhi, and food was part of that battle for distinction. The agricultural riches of Oudh and the Lucknavi love for cream shaped the direction of the region’s food in the ensuing decades. That the evolution of curry, despite its continuing adoption of spices from around the country and world, exists on a regionally particular time frame is one of the greatest insights to be gleaned from Collingham’s detailed history; that the dish has undergone many modifications to suit colonizing tasters is another. Curry’s status as a product of empire, adaptation, an absorption of other cultures, doesn’t make it any less specific to a certain time or place in Indian history. It just makes it clear that India’s past is as inextricable from cultural influence and pushback as the past of curry itself.

Meena Pathak’s introduction to her 2004 cookbook, Flavours of India, both capitalizes on and reacts against the family’s business of U.K.-style curries, by plumbing the past:

Some of my earliest memories are of going to the market with my grandmother in Bombay (now called Mumbai) and watching her haggle with the vegetable sellers to get the best produce … In her house, food was always something that was eaten for taste and enjoyment, not just for nourishment …

And here’s a complementary, family-nostalgia-heavy passage from the introduction of Australian chef Ragini Dey’s 2013 book, Spice Kitchen:

My earliest food memories are of the family lunch table, specifically at my grandparents’ home, where plates of kababs, curries, sweet seasonal vegetables, crunchy salads, crumbly breads, beautiful rice dishes, perky aachars (pickles) and chutney, softened by velvety raitas, were consumed, while mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles compared their favourite recipes and tips for making the best parathas.

From Meera Sodha’s 2015 Made in India: Recipes from an Indian Family Kitchen, another paean to the authentic:

I’ve never lived in India, but I grew up in England eating the same food my ancestors have eaten for hundreds of years and which I still cook in my kitchen, every day.

My family’s home cooking is unrecognizable from a lot of the food that is served up in most curry houses across the U.K.; ours is all at once simple, delicious, and fresh. Real Indian home cooking is largely an unknown cuisine …

Shelina Permalloo, a fellow first-generation child of Mauritians (but born in the U.K. and destined to be winner of the 2012 season of Masterchef, while I am a Canadian who can cook seven things pretty well), introduces her book with another reach into her family’s past, beginning with their family home in Southhampton and ending with a section called ‘Mangoes and Memories’:

Mum always listens to music while cooking and when I think of the times I used to sit on a little stool in the kitchen being her sous chef, my head fills with memories of old Indian songs and traditional Mauritian Sega songs – classics like ‘Bayaboo’ and ‘Li Tourner’ – my mum humming away as she chopped garlic, ginger and onions, the clattering of the rolling pin and the sound of the pressure cooker steaming in the background. Dad would come in and try to dabble with Mum’s cooking, but usually he would just pinch the best bits before it hit the table!

The introductory hook of a cookbook, its raison d’être acheté, must be an explanation of why the recipes matter. In the case of an Indian cookbook, an authentic experience on the plate can be provided only by the authentic experience of the author. Hence the striking similarity between the passages above, where each cookbook author demonstrates that her recipes are, above all, authentic. You can tell, because each begins with an account of being on the inside, within a family that represents an uncorrupted version of a background and nation that other readers and cooks can’t experience, even if they share a parallel family history – these perfected memories of the past promise meals purer than anything a restaurant can dish out.

There’s an episode of the reality TV series Kitchen Nightmares that I think about a lot, a truth just as embarrassing to write as you think it would be. I call the episode ‘Pick-and-Mix,’ and watch it on YouTube frequently. I should first flap my hands here and say that it’s the earlier, U.K. incarnation of the show, Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares, which was narrated by Ramsay, shot without eighty edits in every conversation, and scored with actual music instead of the splashes and screeches that soundtrack the American version, in which every episode seems to be about a broken family coming to terms with how they can love each other while they clean their filthy walk-in fridge and convince themselves they can clear a million dollars of debt by using the microwave less.

Channel 4’s Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares, and this particular episode I’m talking about, Season Five’s ‘The Curry Lounge,’ is full of engineered moments and the occasional sequence of unedited, semi-accidental truth. The premise of the show is that Michelin-starred chef-celeb Gordon shows ailing restaurateurs the way toward financial prosperity and, often, a higher standard of purity in their cooking. The U.K. version lacks the scripted ridiculousness of its American cousin, and this episode’s story ends up highlighting a few different models of ‘the good immigrant’ of the brown U.K. variety, as well as an elegant evasion of the white-saviour narrative. By focusing on telling the brown men in the kitchen that they’ll thrive simply by following their home-cooking instincts instead of pandering to white palates, Gordon saves the day through his higher respect for authenticity.

Nottingham, where the Curry Lounge still exists, is a city dense with I

ndian restaurants and competition. Restaurant owner Arfan Razak, who goes by Raz, is a former pharmaceutical rep whose menu features a ‘Create Your Own Curry’ option, allowing customers to match their favourite sauce with whatever protein they’d like dredged in it. Ramsay chooses to have a chicken korma with prawns, to prove that the kitchen can’t help but make an abomination when the customer is given free reign.

The chef, Zahir Khan, has ‘worked in India’s best hotels,’ as Ramsay’s narration tells us. His kitchen brigade consists of ‘highly skilled’ cooks ‘flown in from India.’ The food that results from the menu they’re given is ‘bland’ and lacks ‘personality,’ and in Ramsay’s confrontation with the chef and the owner, he makes their problem clear: ‘Where that sits connected with Indian, authentic cuisine, it’s game over.’ The story the dishes are telling Ramsay and the viewer can’t be exciting if the eater devises his own meal: part of dining out, particularly in an ‘exotic’ restaurant, is the delight of ceding control to a connoisseur. Ramsay is as apologetic as his persona allows when he explains to the camera why he has the expertise to correct the authenticity flaws in a restaurant that has little to do with his Scottish upbringing or French culinary education: ‘This is a first for me, turning around an Indian restaurant. Now, the basic principles are exactly the same, no matter what the style of cuisine is. But, daunting task. Very excited.’

Ramsay calls the Create Your Own Curry option ‘thousands of years of Indian culture straight out the window,’ which is noble, but also skips over the adjustments that the British Raj made much more recently and that Gordon would likely still consider authentic, or at least delicious (particularly those generously sauced dishes that Indian cooks devised, according to Collingham, to satisfy the British compulsion to start each meal with a soup course). Gordon pins the blame for the pick- and-mix curry option on boss Raz’s desire to please every customer who comes into his restaurant: in the show’s story, this is a man who has abandoned the purity of his roots in order to both please and profit from the white masses of Nottingham.

Curry

Curry