- Home

- Naben Ruthnum

Curry Page 10

Curry Read online

Page 10

‘The character [Brij] in my book is based a little bit on my father,’ explains Malla. ‘My father was able to go back to Kashmir. But for Brij, the inability to go back creates an identity around the place that’s rarefied. And for Ash, Kashmir has become a fantasy land that exists only in stories.

‘The book is an exploration of how identity – not just national but personal, gender, political – is created through storytelling … writing this book I was owning the clichés in order to undermine them.

‘The whole first generation seeking their roots from trauma is a problematic story. It’s a solipsistic way of understanding trauma … By eventually forcing the character into it, and by undermining the script, I wanted to illustrate the falseness of those stories.’

Malla’s previous work successfully evaded addressing the clichés: in the story collection and novel preceding Fugue States, Malla had sidestepped the curry game completely, delivering closely observed and sometimes surreal character-based stories that had little to do with his racial or cultural origin. In the same interview, he describes avoiding writing about his identity partially in reaction to the way ‘South Asian writing is commodified … Writers of colour are expected to explain themselves to a larger [read white] [interviewer’s insertion] audience … I was not comfortable participating in that mechanism.’ Malla’s interviewer, Bhandari, herself of South Asian heritage, transitions from this quotation by writing that in Fugue States ‘Malla finally decided to explore his heritage.’ That ‘finally,’ from a brown reader and writer, is telling – it’s not just the majority-white audience that anticipates identity- and heritage-focused stories from brown novelists and memoirists: it’s the brown audience, too. Bhandari’s interest in this novel that, as she writes, confronts ‘tropes and archetypes head on’ also points to an eagerness on the brown (and, I’d argue, much of the white) audience’s part to read different stories, to have their expectations that a novel by a brown writer is going to be all about heritage, about looking back to the homeland, frustrated.

Nostalgia fuels everything from revivalist rock to rightwing political movements. As American political scientist Mark Lilla has pointed out, European nationalists, the American right, and extremist Islamist organizations all embed a vision of life lived better in the past in their vision of the future. South Asian immigrant fiction, memoir, and cookbooks – all of them contributors to the currybook genre – are often deeply marked by nostalgia, by a drive for discovering the authenticity left behind in another time and place. South Asian Writer is an identity, not just a pair of adjectives and a noun: and it’s an identity that establishes a tacit promise to an audience that is seeking it, whether the author intended it or not. What’s promised? Authenticity, a sense of the past, of a realer elsewhere.

As Changez, the narrator of Mohsin Hamid’s brilliant 2007 novel-in-monologue-form The Reluctant Fundamentalist, realizes in post-9/11 Manhattan, looking back has become part of the cultural order of Western life. As the foundations of his American existence begin to fracture beneath him, he notices everyone around him looking backwards, to a past where he may not belong – it’s only natural that his own gaze, later in the novel, will become fixated on the rear-view.

Possibly this was due to my state of mind, but it seemed to me that America, too, was increasingly giving itself over to a dangerous nostalgia at that time. There was something undeniably retro about the flags and uniforms, about generals addressing cameras in war rooms and newspaper headlines featuring such words as duty and honor. I had always thought of America as a nation that looked forward; for the first time I was struck by its determination to look back. Living in New York was suddenly like living in a film about the Second World War; I, a foreigner, found myself staring out at a set that ought to be viewed not in Technicolor but in grainy black and white. What your fellow countrymen longed for was unclear to me – a time of unquestioned dominance? of safety? of moral certainty? I did not know – but that they were scrambling to don the costumes of another era was apparent. I felt treacherous for wondering whether that era was fictitious, and whether – if it could indeed be animated – it contained a part for someone written like me.

It feels unnecessary to belabour the ‘Make America Great Again’ overtones to the America that Changez sees, but what’s perhaps slightly less evident is the role that Changez has found and that he plays throughout the novel: he is narrating his past, in this long monologue, to an American in the Old Anarkali district of Lahore, Pakistan. That is the part written for him – to discuss the mistake of thinking he had a place in America, and the story of his voyage to the homeland. Hamid is riffing on the currybook, too, without directly acknowledging its touchstones. In this story of a young, successful Pakistani who can’t find happiness or a place in America, against a backdrop of terrorism, menace, and everyday racism, Hamid crafts a sinister homecoming, a nostalgia imposed from the outside that drives his protagonist back to the nation where he came from, and makes storytelling and visitations into the past itself a charged weapon against the American who is hearing his story in a state of heightened alertness and fear. As Changez points out, nostalgia can be ‘dangerous.’ It’s not just classic rock and vanilla milkshakes: it’s a close ally of extremism and racism in America, Pakistan, and the rest of the world.

The restricted stories of brown homecoming and nostalgia that form the tropes and clichés of currybooks don’t reflect the variegated, class-divided, and culturally widespread experiences of brown people in the West. They present a comforting, streamlined, and largely untrue version of what brown people were and are, to a multiracial audience of readers who are supposed to recognize themselves or their neighbours. They also continually point to the fact that brown people aren’t from the West, even if they live in the West, even if they were born in the West. A link to one’s genealogical and geographical roots can be fulfilling and enriching, but when it’s imposed on you from the outside that you’re supposed to know and tell these roots, to be able to present the papers that explain your skin to a waiting audience, the homecoming trip feels a little less heartwarming.

Samad Iqbal, a character in Zadie Smith’s 2000 domestic-cultural epic novel White Teeth, carries out the project that Chanu in Monica Ali’s Brick Lane intended: he brings his offspring back to Bangladesh. Chanu, alone in the old country, peacefully comes to the never-the-same-river-twice realization that his homeland was never the place he remembered it as, and it certainly isn’t the wish-fulfillment he expected when he returns. He’s still himself, in a place that is almost as new to him as England was when he emigrated. Smith’s Samad brings Magid, one of his twin sons, back to Bangladesh. Instead of Samad having produced a tradition-steeped, pious son, Magid becomes an atheist, a scientist, a lover of the modern world. The twin who stays in England, Millat, is the one who has the serious flirtation with fundamentalism and the past, joining a rugged Islamist cult that perpetrates minor acts of terrorism. In keeping with Mark Lilla’s averment that extremism and nostalgia are intimately connected, Millat’s slide into fundamentalism is made possible by his unfamiliarity with the realities of his homeland in combination with his discontentment with London life. His twin has actually made the trip back: the ultimate disillusionment, the actual, inevitably disappointing enactment of homecoming.

A poisonous, crucial element of this imposed expectation is that brown people and their books should look back, into a past and a place that may never have existed. Ash, Malla’s protagonist in Fugue States, is also a writer, and his second novel ‘was supposed to have been “about Kashmir,”’ but his ‘inability to invent characters, resistance to research, misgivings about treating tenuous cultural heritage as material’ prevent him from ever starting this novel. Ash’s father offers his son comments on his attempt at a short story set in Kashmir, remarking on just how many details his son has gotten wrong, from people keeping dogs as pets during the worst of the Troubles to the inclusion of non-existent cobblestoned streets. ‘You have ma

de the city vague. You have missed its particulars. Where is Dal Lake? One must either go to Kashmir so one might write something accurate or one must write about some place one has been and knows. One has a debt to the people of any forgotten or ignored place.’

Brij, a reader with stern expectations of what a book about the homeland should do, may have it right when he talks about the debt a writer owes to the real people who live in the real places he or she writes about: but does this have anything to do with the invisible contract the writer has with the reader? Ash’s (likely bad) short story about Kashmir could still do something for its audience: it would show the disconnected, racialized writer questing for truth in the past, even if he is inventing that past and place as he feels it out. As Ash considers a trip to Kashmir after his father’s death and the discovery that Brij left an unfinished novel of his own behind, he constantly feels warded off by the burden of cliché, by the pressure of the unseen, page-flipping audience: ‘Besides: brown boy’s dad dies, brown boy flees to the fatherland to discover who he really is? No thanks. I’ve seen that movie and it sucks.’ And: ‘Picture it: me scattering the cremains from some mountain, and then honoring his memory by completing the opus. And then what? People read it and are so moved that peace descends on the valley? Or worse, I win a prize?’

The valley, Kashmir, is part of the audience that Ash imagines, with the prize jab denoting the white literary establishment over in this hemisphere. It’s a broad crowd to imagine ‘explaining’ oneself to: and this is the expectation that Malla told his interviewer he sees imposed on books by South Asian writers. Opening the audience question both ways, as his character does, making writing by South Asians an explanation of Westernized brown people to the East, and an explanation of brownness and the eternal truths of the tumultuous homeland to the West, shows just how multivalent a set of coded clichés can be. Telling the same story of brownness over and over doesn’t only express a coherent notion of race and history to white readers, it creates an impression of commonalities among a brown audience who may come from vastly divided pasts and have little in common in their present, other than they ‘all look the same’ in communities where they’re part of a box-tick minority category.

There are near-infinite tellings of South Asian experience possible, a library labyrinth of potential novels about everything from white serial killers to brown university janitors. It’s just that accepting that diasporic identity is as slippery as personal identity is as thrilling, daunting, and worryingly progressive as acknowledging the total unpredictability of the future and the lack of comfort to be found in the past.

Coda

A few years ago, I wrote a story that splinted the fragile ankles of my writing career and pushed me into the world of professionalized writing. I hate getting annoyingly mystical about writing crap, and I will try to avoid it here, but completing this story was the first time that I felt, truly, that I’d written something good. Ray Bradbury often retold the experience of completing his early story ‘The Lake’: ‘When I finished the short story, I burst into tears. I realized that after ten years of writing, I’d finally written something beautiful.’ Thank Christ, I can say that I didn’t cry or come anywhere close when I finished writing my first good story. I just felt helpless and beaten.

If this story wasn’t good enough to leap the rejection pile, if it wasn’t good enough to do something to confirm that my writing wasn’t just a shadow-puppet show in a lightless room, it was time to stop. The piece was both the best I could do and something I’d never done before: a story set in Mauritius. I called it ‘Cinema Rex,’ geographically cheating the location of the movie theatre next to the house where my father had grown up in the fifties – the one next to him was actually called the Majestic, but I couldn’t risk an earnest Jim Carrey sneaking into my phantom reader’s mind. I was twenty-nine and felt depleted by the steady lack of success that typically characterizes the early days of building a writing career. So I took what I told myself was a last shot, with a mixture of repugnant self-pity and genuine hopelessness. I put a story in an envelope and mailed it in to a small literary journal contest.

The force of the idea as it came to me – the boy who lived next to the movie theatre, a portal into a world he wanted to live in, rooted in a place that was trying to hold on to him – felt strong, insistent. As I wrote it out, I felt free of any of the critical doubts I’ve voiced in this book about retreading stories of homecoming, of the homeland, of the past. I knew the shape of the story and what the characters would be doing, and I knew it had more power than most of the scribbling I’d been doing for the past couple of years. Revising it, I knew that it could be received as a currybook-style narrative, but I thought that it was so clearly about a nostalgia-free escape that it was clad against that reading. Wasn’t it?

‘Cinema Rex’ is at the upper end of short-story length and the lower end of novella, with the on-page text telling the story of three boys attending Rex’s opening-night screening of The Night of the Hunter. I was arrested by the idea of a boy growing up next door to a movie theatre and seeing it as a portal into the West, and aligning past and future timelines on the same page to create a sense of each character’s future informing his past. Footnotes leap the reader forward in time, showing the future film careers, deaths, successes, and failures of the boys, two of whom manage to escape Mauritius. That’s where my story strayed from the tropes, I told myself after it was finished: these boys want out, they have as much desire to stay on the island as Clint Eastwood had to remain on Alcatraz, as I had to keep living in Kelowna. They seek a way out of their childhoods through the screen, and they make their escape without wistfully looking back.

But the fucking story itself is a look back. I was flirting with the currybook genre and its tropes simply by having the background I do, drawing on the familial background that I did, and casting a narrative line into a past and setting that are as exotic to me as they are familiar to my parents. Nostalgia is inextricable from a story about leaving the homeland, which means my story is open to the same kind of interpretive lens I’ve put on work by South Asian writers throughout this book. When ‘Cinema Rex’ won one prize and then another, and agents and publishers communicated their interest in me for the first time, I thought I’d expand the story, fill in the interstices between the past and those footnotes, arriving at a full depiction of what became of these kids from the fifties through the nineties, a novel spanning that Mauritian cinema, London squats in ’68, rent-boy life in 1970s Rome for a brown film composer both hiding and using his race, right up to the grotesqueries of 1980s Hollywood. I drafted most of it, showing no one, and received a fair amount of book-industry interest in my inbox and at events, a murmur that has never completely abated.

But a general – while certainly not universal – lack of interest in anything else or anyone else that I was writing about alerted me that I was at risk. Publishers and agents who were initially intrigued that I wrote crime fiction and that many of my other short stories were about contemporary people of various races and social classes, rarely with a South Asian central character, had little interest in that work once they actually saw it. They wanted, it seemed to me, the brown nostalgia book, the one that fit a slot in the publication schedule for readers who like buying that sort of thing.

In Canada, which has a literary industry supported strongly by arts grants and a healthy prize culture funded largely by private and corporate donors, there may be a particular relationship to publishing a currybook. Prominent on my familial shelves when I was growing up were two novels by Mumbaiborn, Canadian-settled Rohinton Mistry: 1991’s Such a Long Journey and 1995’s A Fine Balance. International hits of the highest order, with accolades from the Booker shortlist to Oprah’s Book Club, Mistry’s brown success in Canada at that time was outstripped only by Sri Lankan–born Michael Ondaatje, whose own eighties and nineties megahits In the Skin of a Lion and The English Patient strayed from any blueprint of brown writing by centring on ch

aracters of varying races with no geographical link to the author’s country of origin. Mistry’s big books were Indian-set, and were the high-visibility descendants of novels by South Asian-Canadian authors such as Bharati Mukherjee, whose earliest works centred on ethnic identity and alienation in the West. Mistry’s novels, rooted as they were in India, embedded looking-back as part of the successful narrative of diasporic writing in this country, especially when his success became international.

In a small literary culture fuelled by publishers seeking material with a trackable success record and granting agencies with juries who may tend to favour riffs on what they’ve read before, pieces of writing that strum familiar chords tend to rise to the top. My currybook anxiety is justified: being so invested in avoiding the tropes means some brown writers, like me, or Pasha Malla, may end up tripping over them to the detriment of our own ability to tell our particular stories or, at least, to get them published. What they’re interested in up here in Canada, it seems – at least, it can seem when you’re sending that email to a journal or an agent or a publisher – has a lot to do with how you write about where you ultimately came from, and not about what you write about as a brown Westerner with a collection of different interests and experiences.

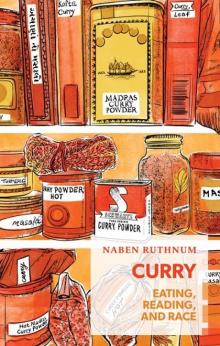

Curry

Curry